Tiptum, the continent on which Tepat sits, is the easternmost and second largest continent on the planet. The continent as a whole stretches from the tropics to the polar regions. Tiptum is divided roughly into two half-continents, known as Lamnûm (the South) and Poknûm (the North). The area where they join, running through Notoq, is sometimes referred to as Nûmtip, the ‘navel’ or ‘waist’ of the continent, or Yôntip, its ‘belt.’ The continent is also divided into east and west by the Tiptum Cordillera, which mostly runs parallel to the eastern coast. It includes the Notoq, Muqali, and Wasak Plateaux, the Muqali mountains, and the interconnecting Amtom Ranges in the northeast. Tepat claims all land south of 37 degrees latitude, as well as land within 50 km on either side of the Pemet, Lower Phitim, and Luqtal rivers not otherwise within that range.

The Yuk Sôl or Inner Sea is a very large salt-water body situated just north of the equator and enclosed almost entirely by the continent of Tiptum. As part of the continental plate of Tiptum, it is much shallower than the open ocean, and has its own circulation patterns. Nourished by the heavy discharge of Tiptum’s rivers, and tropical rain, it is less salty than the open ocean. It is also home to many unique species of fish, and the coastal areas are rimmed by vast undersea sponge forests. The lack of exchange with the ocean traps heat, making the Sea the warmest one in the world. Numerous hurricanes spawn in or near the Yuk Sôl, but because they follow westerly paths out of the sea, they rarely threaten areas of Tiptum itself.

Fog fills the cliffs and fjords to the latitude of the Conciliarity’s northern border, and further. At that point, the clouds are nigh continuous, such that the sky over the forests is just gray on green - faint gray above, dark green below. Prior to Tepatic colonists, most of the inhabitants were Taknic, suggested by the lack of labial sounds other than [w] in placenames.

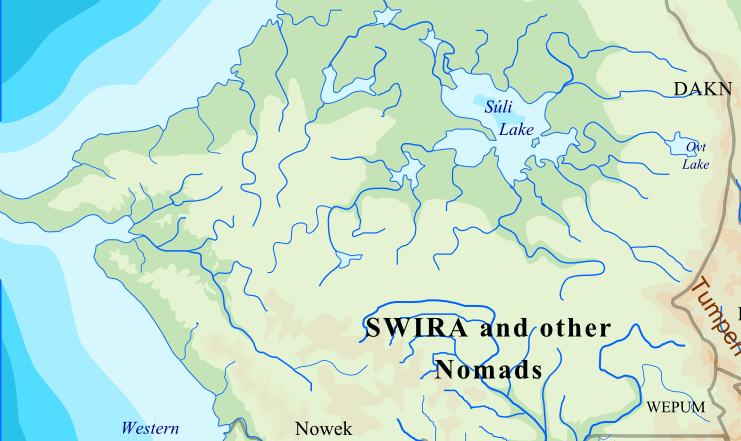

The fog stops when it hits the mountains. Past them, clear, cold, and dry skies observe the progression of airy pines to burly shrubs and finally mere bristles of grass. By that time though, it has reached the Eastern Range and Tumpen, and pines reclaim their rank. Cold desert appears on the slops of the Tumpen mountains as they approach the steppes. Further north, in the Lake-and-River region, dense forest predominates, criss-cut by ziggy rivers with paths so turning that they themselves barely know which way they drain. This area is centered on one huge lake, Lake Súli, the largest lake in Tiptum and one of the largest in the world. Most of the Lake and rivers are edged by wetlands. Not exactly great for human settlements, but they host many migrating birds, which people depend on to hunt seasonally. The far north is mostly tundra, with humans turning to the sea for sustenance. The large northern peninsula known as the ‘Far Handle’ (Lepthel) is barren, and some areas are almost continuously covered with ice. Impossible though it may seem, Taknic hunters occasionally venture even here.

The lifeline of Tepat is the great river valley cutting

diagonally through its center. The two major rivers of the north,

the Pemet and Phitim, merge in

the center of the country at Xhangtyel, the

'Meeting of Waters,' to form the Yot Klun, 'Wide

River.' The Klun is also Tyel Kyet or Yot

Kyet, possibly meaning 'Braided River' and referring to

the fact that the waters of the two rivers are ‘twisted’ together

here - or that the lower reaches of the river, winding and

surrounded by oxbow lakes, resemble braided hair.

Different regions of Tepat have different seasonal patterns of precipitation. The eastern part, with a humid subtropical climate, gets precipitation mainly in the summer in the form of thunderstorms, with less in winter. The western regions with more Mediterranean climates have dry summers with rain in the winter. In the middle of Tepat where the two climate zones transition, there is a zone with two annual peaks in precipitation, in the summer, and the winter. By coincidence, this area corresponds largely to the drainage basin of the Klun River. The availability of so much water year-round made it ideal for agriculture and transport, however, floods were also a risk. The eastern branch of the upper part of the Phitim River, through which most of the country’s thunderstorms and tornadoes pass, was known as the Winds’ Road, or Khat i-Xyul.

The southern part of Tiptum is known Hanam. The

Klun River exits here in a vast delta, with a family of small

muddy lakes around it. This is the muggiest part of Tepat. The Lenuk

people who lived here in ancient times lived primarily in boats,

traveling the labyrinth of lakes and rivers.

The western parts of Tepat have a Mediterranean climate and a

largely chaparral vegetation, which gets sparser toward the

southwest as it merges into desert. Oak is a big component of the

chaparral in the dry hills. It is also full of dark green,

thick-leaved or scaly evergreen shrubs. In the state of nature,

these shrublands are subject to periodic burns. Some of the plants

reproduce with seeds encased in very thick, hard hulls that do not

open until scorched by flames. Volatile oils in the leaves

facilitate combustion. They are also valued as medicines and

flavoring in wines and sauces.

Twin lighthouses, Tôqhaw Lam and

Pok, are found at each end of the strait known as

Tôlman, "Fog Turn," where ships from the south

turn into the Inner Sea. The fog that rolls in at night vanishes

by noon without ever touching the ground, leaving the sun with

perfect clarity for the rest of the day. Following the glow, ships

from the Outside dock safely for the night, have their cargo

inspected by Tepat in the morning, and wait for the clarity of

afternoon to round the point into the Inner Sea. Such is the whole

west coast, south and north of it. Such is the whole west coast,

south and north of it. Lôkh i-Mûn,

Warning Island is nearly midway between the prongs of Tiptum at

the entrance to the Sea.

South of the straits is a desert peninsula Pet. Despite the millions of water droplets hanging over it each morning, this is the driest region of Tiptum. Some plants do actually grow here, all of these which are efficiently exploited by the native Heiepe, who inhabited the peninsula before it was colonized by Tepat in its attempt to control shipping through the strait.

The ubiquitous ground cover, in distant patches, is needle grass (Yuktepat: khut-chut), which fends off all foragers with stiff, sharp-pointed leaves. Brave humans have nevertheless collected it in order to sew clothes. Other residents include the only slightly more appetizing spiky fatleafs (ti-yôp-phuk) and bladeleafs (ti-yôp-lam). The fatleafs’ bulbous leaves are covered with short thorns that spiral upward toward the tip of the leaf. Every few years they produce flowers on a single tall stalk. Those patient enough to gather the leaves and cut off the thorns can eat them, or pulp them to make juice or beer. Bladeleafs’ leaves are nested within each other, with edges so sharp the natives have used dried ones as hunting weapons. The Heiepe make bowls out of the clustered plant leaves, which they cover with cloth and set outside at night. The fog condenses in the cloth and the leaves as dew, by which the people obtain a very useful substance known as water.

The southwest desert areas of Tiptum are typically dry and receive little rain, but are affected by neighboring tropical weather systems. The region receives most of its precipitation in brief and sudden torrents from west-moving tropical storms that begin in the Inner Sea. These storms often dissipate when they reach the desert, but sometimes they reform and gain strength on the other side of the ocean, swelling into hurricanes that end up blasting the coasts of Aipura and Tricunia.

The eastern mountains tend to be wooded by conifers such as

spruce, fir, pine, larch, hemlock, and yew. There is generally a

purely forested strip bordering the mountains in their lower and

more level reaches. Such forests are oftentimes mixed forests,

containing deciduous broadleaves. The broadleaves tend to drop off

as one climbs up, the steeper ridges being mostly the

aforementioned airy pines, and the summits generally bald and

snowy. The mountains are also home to mountain goats and bears, as

well as the boss cat.

As these mountains run along the only major tectonic fault line

in Tiptum, they are subject to occasional earthquakes, leading to

occasional avalanches and landslides, and have limited volcanic

activity. It is believed that Tepat’s legendary Hyum’s

Cauldron, a lake of fire, may have been a reference to

some formerly active volcano in this mountain chain.

Notoq is situated on a plateau, part of the mountain chain

running north and south through the continent. The border between

Tepat and Notoq is defined by the Xhop River.

The watershed boundary of the Cordillera separates Notoq from

Kutsu. Diamond Pass, the aorta of international

transport and commerce in Tepat, marks a four-way boundary among

Tepat, Notoq, Kutsu, and Pahs.

The majority of Notoq is a plateau, somewhat lower than Muqali’s, composed of hard volcanic rock overlain on softer deposits. This is in contrast to Wasak, much of which is sedimentary rock, and eroded by water into deep-cut canyons. Like part of the Muqali plateau, it was probably deposited over aeons by floods of molten rock, perhaps embedded in long-lost and distorted memory reflected in myths of a Great Flood of Fire. Where this stony layer ends, often abruptly, a series of falls are produced, such as those at Ninil and Xhatim. Ninil originally had a pine forest surrounding it, and two especially old and large pines grew on either side of the fall. They were torn down during the Shattered Land, but the name and memory remains. Xhatim is named for two fang-like projections of rock, between which the stream jets out.

Southeastern regions of Notoq are home to partially assimilated minority peoples who speak lesser Tepatic and Muqalic languages. They were used as a pretext by Muqali for invading Notoq to annex the land, followed by the “liberation” of the minorities and a program of forced de-Notoqification. This ushered in the Age of the Iron Fists, in which several authoritarian regimes emerged around Tiptum.

The Muqali plateau and

adjacent mountains are the most elevated region in Tiptum. Along

its eastern border, the Qhalucutl Range is the

longest and highest mountain range in Tepat. Qatlak P’awu,

'The Dragon's Fang,' is approximately 6000m high, and the highest

mountain in Tiptum. In the northeast, along the border with Kutsu,

is the Hayalwa Range, almost as high. The

country is home to a large number of precipitous valleys, the

result of glaciers which extended very far downhill during the ice

age. As clouds work their way sweating up the slopes, they dump

heavy rainfall on the western margins of Muqali. As a consequence,

parts of the lower slopes are densely treed, though they resemble

the cool fog forests of Nowek more than the warm jungles downhill.

Even further up, and in drier interior areas, the forests turn

into humble pines. Grasses and shrubs top those, then moss and

lichens, and by the top, some of the mountains are completely

covered in glaciers. Being close to the equator, the seasons are

slight and day and night remain nigh equal throughout the year,

but being highly elevated, temperatures are cool and even frosty,

being usually 10° C cooler than the lowlands.

Amtom refers to the eastern coast, particularly of the northern

half of the continent. Unlike the open areas to the west, in the

east, the mountains abut very closely to the sea, and the

shoreline is much more irregular than other parts of the

continent. Compared to Tepat, Amtom streams are typically swift,

deep, and narrow. Off the coast lies a subduction zone, which is

capable of producing massive earthquakes, at least one per

century. The East Coast is thus sometimes threatened by tsunami,

although mitigated by the aptly-named Barrier Islands

(not yet on the map). The giant waves, rising from the trench,

wash over the (less-populated) eastern shores of the Barrier

Islands, but dissipate before passing through the straits toward

the main Amtomic coast.

During the winter, warm dry winds roll over the mountain slopes,

keeping the coast warm and largely free of ice and snow, although

they also increase the risk of fires. During the summer, rain is

provided mostly in the form of afternoon thunderstorms (though

milder than in Tepat), and less frequently, but more dramatically,

in the form of typhoons blown in from the equatorial waters to the

east.

The mountainous interior is forested by large deciduous trees, largely the same species found in Eastern Tepat, and at higher elevations and latitudes, needleleaf trees. There are great differences between the boreal forests in the north, and tropical ones in the south. Offshore, the islands have essentially the same profile of trees and wildlife, though with some unique species here and there in the Barriers.

The tropical region encompassing the provinces (or states) of Nusam

and Wetey may be collectively referred to as Thoyot,

which is presumed to be a corruption of they yot, or “four

rivers,” referring to four major rivers that drain the region and

exit to the sea nearby each other. The Tulpaya

(Muqali, “Great River”) is the longest and widest, and one of two

major rivers that originate in Muqali and drain southwest through

the forested lowlands into the Yuk Sôl. (The other big river is

the Cipcuya.) It is also, narrowly, behind the

Phitim river system as the longest river system in Tiptum. The

Tulpaya originates from a mountain spring in Northern Muqali which

feeds 'Worldbirth' Lake, Taluk Niqtawu. It exits

the lake and flows in a broad arc southward and westward into the

forested area and reaches the sea at a mere one degree north of

the equator. Its biggest tributary is the Milk’it,

which originates in the Huttha region of

southern Muqali and turns northwest to join the Tulpaya near the

foothills.

The entire region is warm year-round and covered with forests.

These include true tropical rainforests in the lowlands along the

coast and the river banks, sometimes extending out into the water

as swamps. Further inland they become more savannah-like, before

thickening again into cooler, misty cloud forests toward the

foothills of the mountains. The forests finally thin out again

into perverted shrubs as one reaches the proper Muqali region. The

tropical grasslands are characterized by frequent lumpy

pampas-grass-like clumps and tussocks, and more occasionally

various heights of palms, grass-trees, and other odd and gangly

monocots, besides thorned acacia or mesquite trees.

In the southeast corner of the tropics, there is a spur of land which offers a harbor safe from destructive sea waves, allowing a port to be built there, and evolve into a big city and a major spot on the international sea shipping lanes.

Reguándóy domum